Writing Tactics

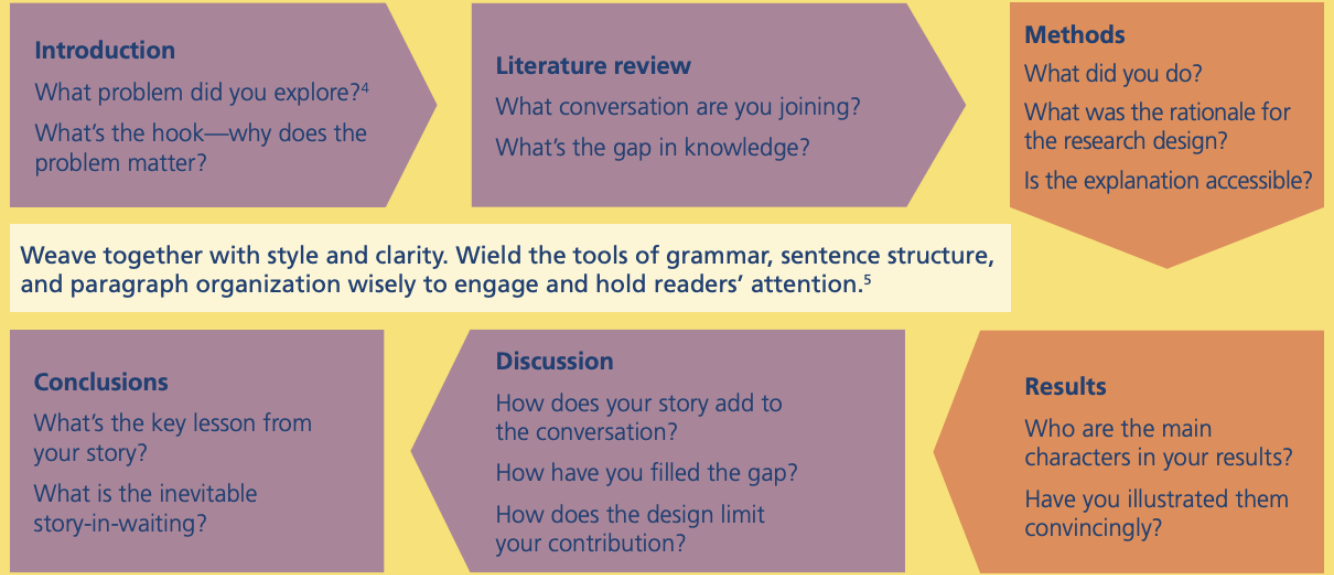

Write a paper/article

- Story/study

- IMRAD

Consult recent articles in target journal!

Frontload your argument.

Introduction

- General background/problem

- Specific focus/problem

- Why is the specific problem unresolved?

- My idea (sell it as obvious)

- Hypothesis

- Aim/objectives

Methods

Using this section, it should be possible to reproduce the results.

Results

Should be like a walk through an art-gallery.

Discussion

- Recap; Summarize findings. ”Long abstract of Introduction and Results”.

- Findings in context of previous research. Three implications max.

- How does your story add to the conversation?

- How have you filled the gap?

- Remaining issues, e.g.: How does the design limit your contribution? Directions for future research

Conclusion

- What’s the key lesson from your story?

- What is the inevitable story-in-waiting?

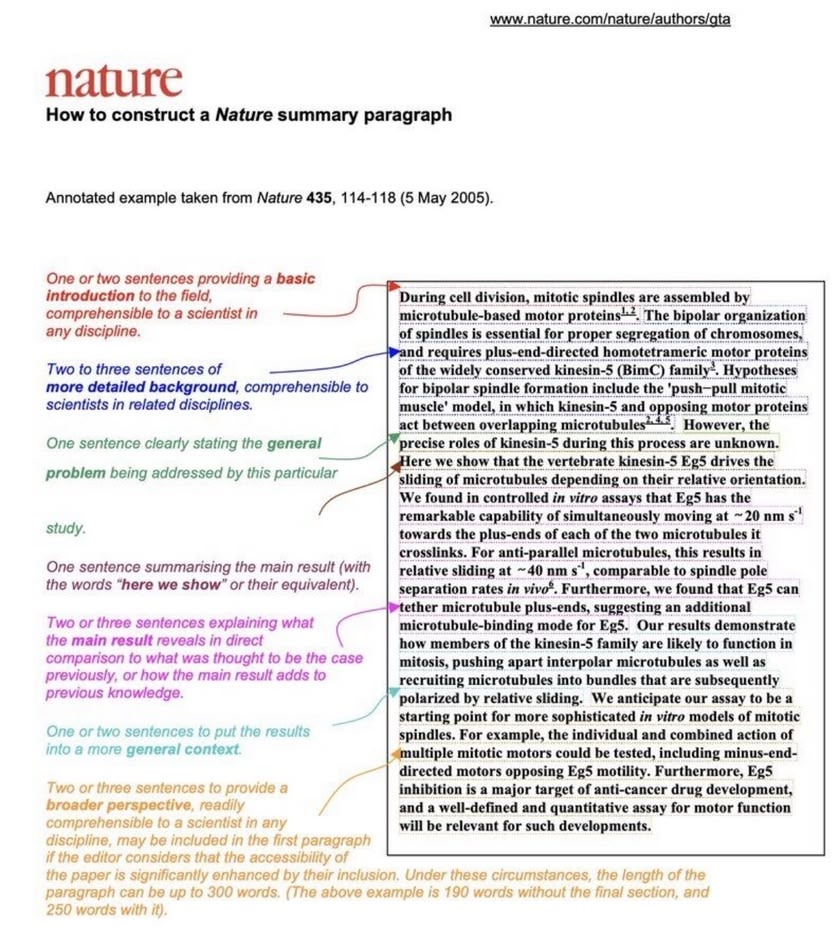

Abstract: after paper is done

- A conference abstract should be a coherent stand-alone piece. By simply copy-pasting sentences from different sections of a manuscript, you risk having a disjointed and incoherent abstract.

- DO NOT USE ALL CAPS FOR YOUR ABSTRACT TITLE.

- Minimize the use of acronyms. If you absolutely must use acronyms:

- Do not include acronyms in your title unless it’s one that EVERYONE in the field will know.

- Define every acronym before you use it. Don’t assume that others will know what you mean.

- Do not recreate (new) acronyms for a phrase when one already exists and is conventionally used.

- Do not use more than 2 acronyms in a sentence.

- Provide a brief description of existing literature and explain the novelty of the current work in your intro.

- State your goals for the study in the last sentence of your abstract intro. This will help orient reviewers as they go through your methods and results.

- Summarize your key findings in the first sentence of your discussion/conclusions. This lets reviewers know what you want them to take away from your study.

- Include figures and quantitative descriptions/statistics in your results that clearly support your big picture conclusions.

- Most important, remember that reviewers may not be an expert in your specific research topic. Prepare your abstract so that any researcher in your general field will be able to follow along and understand your key findings.

Typography

practicaltypography.com

typewolf.com

prowebtype.com

https://www.supremo.co.uk/typeterms/

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

The four most important typographic considerations for body text are point size, line spacing, line length, and font, because those choices determine how the body text looks.

- Point size should be 10–12 points in printed documents, 15–25 pixels on the web.

- If you’re not required to use 12 point, don’t. Try sizes down to 10 point, including intermediate sizes like 10.5 and 11.5 point

- Line spacing should be 120–145% of the point size.

- On screen, dark-gray text can be more comfortable to read than black text.

- The average line length should be 45–90 characters (including spaces).

- Use “curly” “quotation” “marks”, not straight ones.

- Use bold or italic as little as possible, and not together.

- With a serif font, use italic for gentle emphasis, or bold for heavier emphasis.

- With a sans serif font, skip italic and use bold for emphasis.

- Yet another option for emphasis is to increase the font size slightly. Move up in half-point increments until you get the emphasis you need.

- Never underline, except perhaps for web links.

- ALL CAPS, bold, and italic are fine for less than one line of text, not more.

- Use centered text sparingly.

- Your Headings Aren’t Titles, Avoid Title Case (except for actual Titles).

- Use the smallest point-size increment necessary to make a visible difference. If your text is set in 12 point, you needn’t go up to 14 or 15 point. Try a smaller increase—to 12.5 or 13 point.

- Don’t use more than three levels of headings.

- Headings are signposts for readers that reveal the structure of your argument, not you document. Headings that announce every topic, subtopic, minitopic, and microtopic are exhausting. If you write from an outline, that can be a good starting point for your headings, but don’t stop there—simplify it further.

- Put only one space between sentences.

- Don’t use multiple word spaces or other white-space characters in a row.

- If you don’t have real small caps, don’t use them at all.

- Use 5–12% extra letterspacing with ALL CAPS and small caps.

- Kerning should always be turned on.

- Use first-line indents that are one to four times the point size of the text, or use 4–10 points of space between paragraphs. Don’t use both.

- Always use hyphenation with justified text.

- Don’t confuse hyphens (-) and dashes(–, —), and don’t use multiple hyphens as a dash.

- Use ampersands (&) sparingly, unless included in a proper name.

- Use proper symbols (e.g. ellipses …)—not alphabetic approximations.

- In a document longer than three pages, one exclamation point is plenty.

- Put a nonbreaking space

- After paragraphs

- After section marks

- Between value and unit (e.g., 1 mg)

- After reference marks (Fig. 3, Figure 4)

- After titles (Prof. Doe)

- (Parentheses), [brackets], and {braces} should generally not adopt the formatting of the surrounded material.

- To make a signature line, hold down the underscore (_) key until you get the length you need.

Figures

Ideally, each figure should answer only one question. You may have performed multiple independent experiments to answer one research question. The results of these independent experiments can be combined into a multi-panel figure, with one overarching declarative title.

How to write a figure caption

Figure captions should be standalone, i.e., descriptive enough to be understood without having to refer to the main text.

Effective captions typically include the following elements:

A declarative title, i.e. the main conclusion of the figure. Can be in bold font.

A brief description of the methods necessary to understand the figure without having to refer to the main text

Statistical information (avrage, range, sample sizes, number of replicates, asterisks denoting P-values, statistical tests, etc.)

Explanations of what any different markers represent. If possible, describe the figure elements in a legend and not in the caption

Definitions of any abbreviations

References to any table where data was given.

DO NOT simply restate information already given in the figure or analysis of the data.